A Little Boy at Christ's Christmas Tree

Dostoevsky's well-known story is prefaced, here, by the no less touching, if perhaps lesser known, German Christmas poem that inspired it, in an English translation.

Writes Dostoevsky biographer, Joseph Frank: ‘The first mention of [Dostoevsky’s] sketch in his notebooks, dated December 30 [O.S., 1875 - DPC], reads: “The Christmas tree. The small boy in Rückert” [...] Friedrich Rückert [1788 - 1866], a minor German poet, had composed the prose poem, The Orphaned Child’s Christmas (Des fremden Kindes Heiliger Christ [The Strange Child's Holy Christ, in the translation below]). Dostoevsky had lived in Germany, where its recital was a standard feature of Christmas festivities (much like Dickens’s A Christmas Carol in English-speaking lands). The thematic similarity of Dostoevsky’s story and the poem was first pointed out by G. M. Fridlender [in 1964].’1 Frank goes on to summarize and compare the respective works (by Rückert and Dostoevsky). But, if the reader’s thirst to read an actual translation of the German poem has thus been elicited, it is left unquenched. Nor has the internet filled the gap, as far as we are aware (in either English, Romanian, or even Russian) - at least not in contexts related to Dostoevsky, thus far.

Fortunately, Friedrich Rückert’s poem has been put to music by his contemporary Carl Loewe (1796 - 1869). As such, it has become quite well known in the circle of German Lieder lovers (several outstanding renderings are available online, such as by Carl Erb.) In the same circle, we can also find the poem in an English translation, to accompany the Dostoevsky story, that is re-posted further down below:

Friedrich Rückert

The Strange Child's Holy Christ

A strange child runs

Hastily through a town

On the Christmas Eve

To watch the candles

Which are lighted.

It stops at every house

And sees the bright rooms,

The ones inside, they're looking out,

The trees full of light;

Its heart was bleeding at the sight.

The little child cries and says:

“Today all children have

A small tree and a light

And takes delight in them;

Only I'm missing them!

In my brother's and sister's hand,

When I was sitting at home,

There also burnt one for me,

But here I'm forgotten,

In this foreign country!

Won't anyone open the door to me

And offer me a rest?

Isn't there any small corner

In all the houses,

Even not a very small one?

Won't anyone open the door to me?

I don't want anything for myself;

I just want to feast my eyes

On the look of the others'

Christmas presents.”

It knocks at gates and doors,

At windows and at shutters;

But no one steps out

To invite the little child;

Inside they just don't listen.

Every father is just thinking

Of his own children now;

The mother gives them presents,

She's thinking neither more nor less;

But no one is thinking of the little child.

“Dear Holy Christ,

I have no mother and no father,

If you don't take their place.

O, be my adviser,

If everyone forgets me here!”

The little child rubs its hands,

They are just chilled,

It covers itself with its dress

And waits in the narrow lane,

Turning the eyes to its end.

There another child comes

Walking through the narrow lane,

Holding a light,

Wearing a white dress so plain;

How lovely it sounds when it says:

“I am the Holy Christ,

Once I also was a child

as you are a child today.

I won't forget you

if everyone else forgets you.”

The child took it for a dream;

Little angels were reaching

From the tree for the child,

Pulling it softly

Up to the bright sphere.

The strange little child

Has found its home now

With its Holy Christ.

And what has happened here,

There it easily forgets.

Brings to mind the Psalm: “When my father and my mother forsake me, then the Lord will take me up.” As does the Dostoevsky story inspired by Rückert (reposted here with minimal editing, as it previously appeared in the DPC series, on karamazov.ro):

Here is a Christmas story consonant with the idea that all real joy is hidden in the Cross ... Does it not also read almost like an alternative epilogue to Nellie's story? Is it not more timely today than yesterday, this year than yesteryear? But let us also notice, with Met. Anthony Khrapovitsky, its inner regenerative power:

'We have spoken of the prophetic heart, of man's soul which knows tenfold more than "the person itself." It is in this soul, according to its very nature, and also owing to the recollections of childhood preserved, in this soul, even disfigured by passions, lies, and theomachia [fighting against God], that there still remains a deep penchant for holy salutary compassion. If only man would not rudely repulse this sacred emotion, but would follow its indications... The author is not preaching "rosy Christianity"…: his task is to persuade people of the possibility of regeneration offered to them by God and their own soul; their using it depends on their free will... [W]e are convinced that all the listeners, and we hope most readers, of the moving story of Dostoevsky "A Little Boy at Christ's Christmas Tree" should be included [among those "whose hearts were softened"]… [T]he author, and sometimes his friend, the writer [D.V.] Grigorivich, read [this story] at literary gatherings. On these occasions, tears of Christian compassion for the little orphan, freezing under the lighted windows of a lordly house where children enjoyed themselves around the Christmas tree, welled up in the eyes of many even of the male listeners [among whom the young Alexey, later Vladika Anthony Khrapovitsky, already an ardent admirer of our writer, might have been present more than once], not to mention most of the female ones. Christ the Saviour came to the boy and carried him to heaven to enjoy an eternal Christmas. He was met there by his mother, who had died an hour earlier in the basement; her corpse, growing cold, had frightened the child. This is how strong compassion is. Not for nothing does our author write: “if you pity an unprotected being, you will get attached to it, and strongly attached” (The Adolescent.)' (Transl. by Ludmila Koehler)

***

F.M. Dostoevsky

A LITTLE BOY AT CHRIST's CHRISTMAS TREE

(from The Diary Of A Writer, January 1876; transl. by Boris Brasol, 1919; illustrated pages from the 1885 Russian edition for children available here)

But I am a novelist, and it seems that one "story" I did invent myself. Why did I say "it seems," since I know for certain that I did actually invent it; yet I keep fancying that this happened somewhere, once upon a time, precisely on Christmas Eve, in some huge city during a bitter frost.

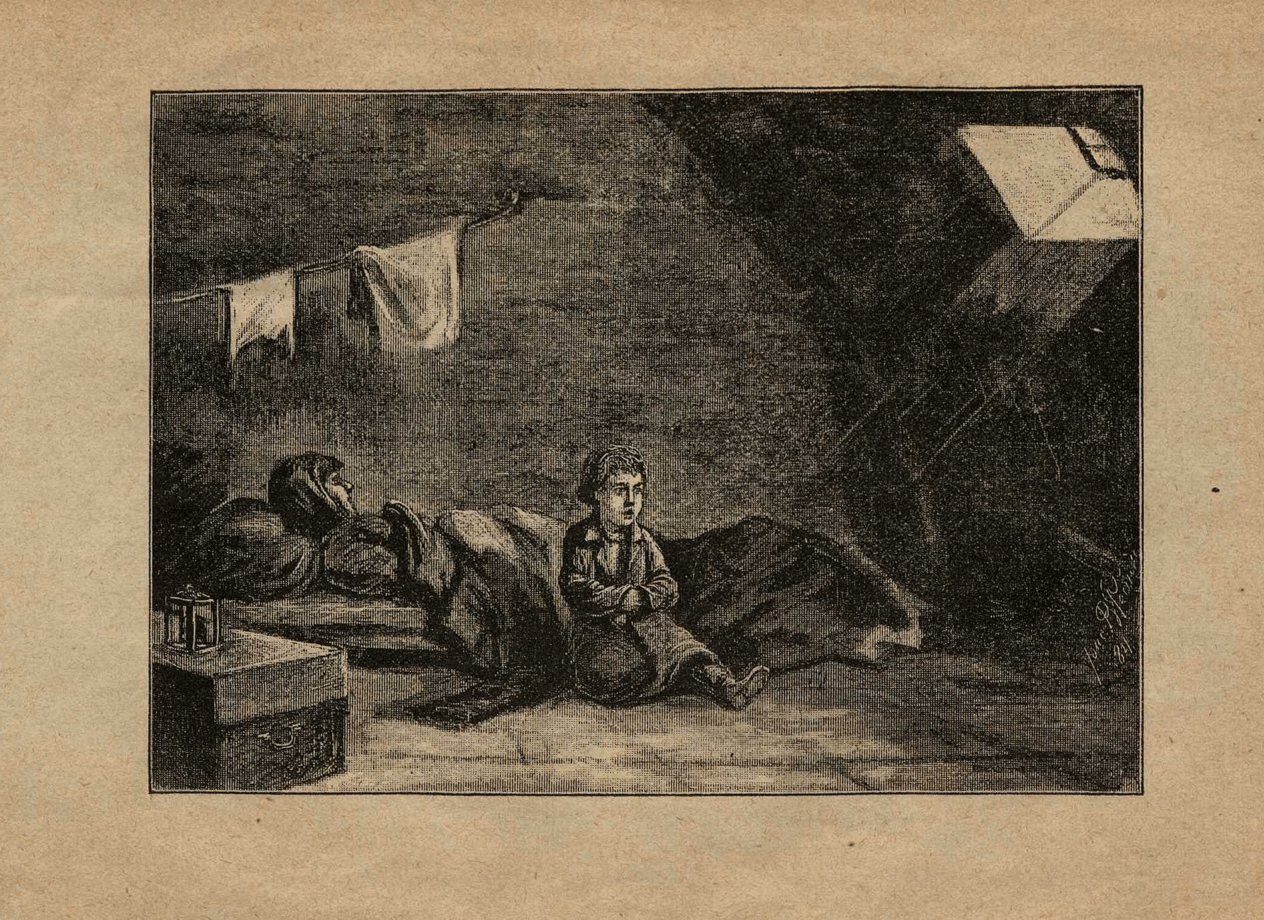

I dreamed of a little boy -very little- about six, or even younger. This little boy woke up one morning in a damp, cold basement. He was clad in a shabby dressing gown of some kind, and he was shivering. Sitting in the corner on a chest, wearily he kept blowing out his breath, letting it escape from his mouth, and it amused him to watch the vapor flow through the air. But he was very hungry.

Several times that morning he came up to the bedstead, where his sick mother lay on bedding thin as a pancake, with a bundle of some sort under her bead for a pillow.

How did she happen to be here? -She may have come with her little boy from some faraway town, and then suddenly she had fallen ill.

Two days ago the landlady of this wretched hovel had been seized by the police; most of the tenants had scattered in all directions - it was the holiday season - and now there remained only two. The peddler was still there, but he had been lying in a drunken stupor for more than twenty-four hours, not even having waited for the holiday to come. In another corner of the lodging an eighty year-old woman was moaning with rheumatism. In days past she had been a children's nurse somewhere. Now she was dying in solitude, moaning and sighing continuously and grumbling at the boy so that he grew too frightened to come near her. Somehow he had managed to find water in the entrance hall, with which to appease his thirst : but nowhere was he able to discover as much as a crust of bread. Time after time he came up to his mother, trying in vain to awaken her. As it grew dark, dread fell upon him. Though it was late evening, the candle was not yet lit. Fumbling over his mother's face he began to wonder why she lay so quiet, and why she felt as cold as the wall. "It's rather chilly in here," he said to himself.... For a moment he stood still, unconsciously resting his hand on the shoulder of the dead woman. Then he began to breathe on his tiny fingers in an attempt to warm them, and, suddenly, coming upon his little cap that lay on the bedstead, he groped along cautiously and quietly made his way out of the basement. This he would have done earlier had he not been so afraid of the big dog upstairs on the staircase, which kept howling all day long in front of a neighbor's door. Now the dog was gone, and in a moment he was out in the street.

"My God, what a city!" - Never before had he seen anything like this. There, in the place from which he had come, at night, everything was plunged into dark gloom - just a single lamp-post in the whole street! Humble wooden houses were closed in by shutters; no sooner did dusk descend than there was no one in sight; people locked themselves up in their homes, and only big packs of dogs - hundreds and thousands of them - howled and barked all night. Ah, but out there it was so warm, and there he had been given something to eat, while here.... "Dear God, I do wish I had something to eat!" - And here - what a thundering noise! What dazzling light! What crowds of people and horses and carriages! And what biting frost! What frost! Vapor, which at once turned cold, burst forth in thick clouds from the horses' hot-breathing muzzles. Horseshoes tinkle as they strike the stones through the fluffy snow. And men pushing each other about.... "But, good heavens, how hungry I am! I wish I had just a tiny bit of something to eat!" And suddenly he felt a sharp pain in his little fingers. A policeman passed by and turned his head away, so as not to take notice of the boy.

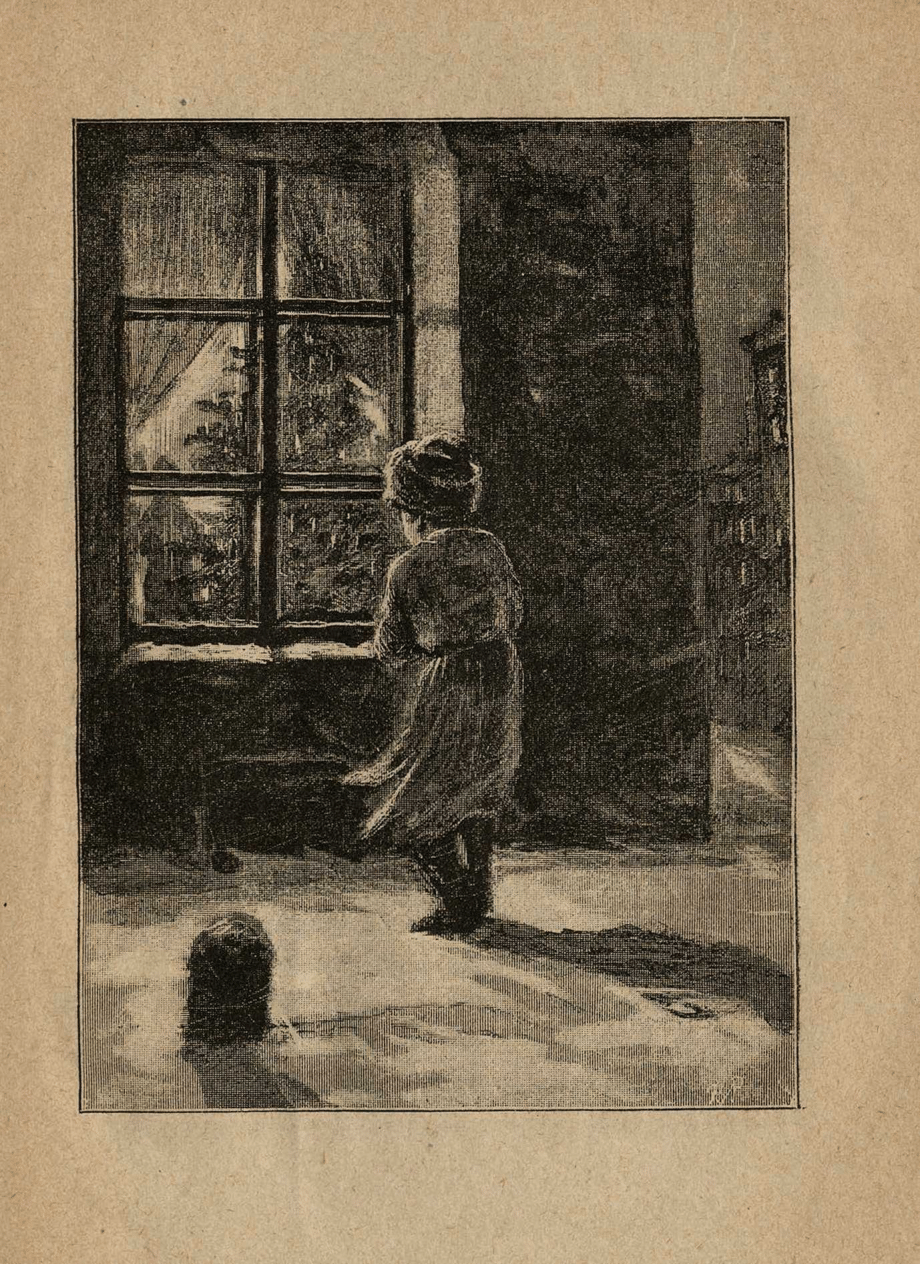

"And here is another street. -Oh, how wide it is : Here I'll surely be run over! And how people shout and run and drive along I And what floods of light! Light everywhere! Look, what's this? Oh, what a huge window and, beyond it, a hall with a tree reaching up to the ceiling. It's a Christmas tree covered with gleaming lights, with sparkling bits of gold paper and apples, and all around are little dolls, toy-horses. Lots of beautifully dressed, neat children running about the hall; they laugh and play, and they eat and drink something. And see , over there, that little girl - now she starts to dance with a boy! What a pretty little girl she is! And just listen to the music! You can hear it from inside, coming through the window!"

The little boy gazes and gazes and wonders; he even starts laughing, but... his toes begin to hurt, while the little fingers on his hand have grown quite red-they won't bend any longer, and it hurts to move them. And when at last he became fully aware of the sharp pain in his fingers, he burst into tears and set off running.

Presently, through another window, he catches sight of a room, with trees standing in it, and tables loaded with cakes, all sorts of cakes - almond cakes, red cakes, yellow cakes!... Four beautifully dressed ladies are sitting in the room; whoever enters it is given a cake.... Every minute the door opens, and many gentlemen come in from the outside to visit these ladies. The boy stole up, quickly pushed the door open, and sidled in. Oh, how they started shouting at him and motioning him out! One of the ladies hurried toward him, thrust a small copper coin into his hand, but she opened the door into the street. How frightened he was! The coin rolled from his hand, bouncing down the steps he was just unable to bend his little red fingers to hold on to it.

Very fast, the little boy ran away, and quickly he started going, but he himself did not know whither to go. Once more he was ready to cry, but he was so frightened that he just kept on running and running, and blowing on his cold little hands. How dreadfully lonesome he felt, and suddenly despair clutched at his heart.

But lo! -What's going on here? -In front of a window people are standing crowded together, lost in admiration... Inside they see three tiny dolls, all dressed up in little red and green frocks, so real that they seem alive! A kindly-looking old man is sitting there, as if playing on a big violin; and next to him-two other men are playing small violins, swinging their heads to the rhythm of the music; they look at each other, their lips move, and they talk - they really do, but one simply can't hear them through the window pane.

At first the little boy thought that these moving figures were alive, but when at last he realized that they were only small puppets, he burst into laughter. He had never seen such figurines, and he didn't even know that such existed! He felt like crying, and yet the dolls looked so funny to him - oh, how funny!

Suddenly he felt as if somebody grabbed him by his dressing gown: a big bully of a boy, standing close by, without warning, struck him on the head, tore off his cap and kicked him violently. The little fellow fell down, and the people around began shouting. Scared to death, he jumped quickly to his feet and scampered off. All of a sudden he found himself in a strange courtyard under the vault of a gateway, and leaped behind a pile of kindling wood: "Here they won't find me! Besides, it's dark here!"

He sank down and huddled himself up in a small heap, but he could hardly catch his breath for fright. But presently a sensation of happiness crept over his whole being : his little hands and feet suddenly stopped aching, and once more he felt as comfortable and warm as on a hearth. But hardly a moment later a shudder convulsed him: "Ah, I almost fell asleep. Well, I 'll stay here awhile, and then I'll get back to look at the puppets" - the little boy said to himself, and the memory of the pretty dolls made him smile: "They seem just as though they're alive!" And all of a sudden he seemed to hear the voice of his mother, leaning over him and singing a song. "Mother dear, I'm just dozing. Oh, how wonderful it is to sleep here!"

Then a gentle voice whispered above him: "Come, little boy, come along with me! Come to see a Christmas tree!"

His first thought was that it might be his mama still speaking to him, but no - this wasn't she. Who, then, could it be ? He saw no one, and yet, in the darkness, someone was hovering over him and tenderly clasping him in his arms.... The little boy stretched out his arms and... an instant later -"Oh, what dazzling light! Oh, what a Christmas tree! Why, it can't be a Christmas tree," for he had never seen such trees.

Where is he now? -Everything sparkles and glitters and shines, and scattered all over are tiny dolls - no, they are little boys and girls, only they are so luminous, and they all fly around him; they embrace him and lift him up; they carry him along, and now he flies, too. And he sees: yonder is his mother; she looks at him, smiling at him so happily. "Oh , Mother! Mother! How beautiful it is here!" -exclaimed the little boy, and again he begins to kiss the children; he can hardly wait to tell them about those wee puppets behind the glass of the window.

"Who are you, little boys ? Who are you, little girls?" -he asks them, smilingly, and he feels that he loves them all. "This is Christ's Christmas Tree," -they tell him. "On this day of the year Christ always has a Christmas Tree for those little children who have no Christmas tree of their own."

And then he learned that these little boys and girls were all once children like himself, but some of them have frozen to death in those baskets in which they had been left at the doors of Petersburg officials; others had perished in miserable hospital wards; still others had died at the dried-up breasts of their famine-stricken mothers (during the Samara famine); these, again, had choked to death from stench in third-class railroad cars. Now they are all here, all like little angels, and they are are with Christ, and He is in their midst, holding out His hands to them and to their sinful mothers.... And the mothers of these babes, they all stand there, a short distance off, and weep: each one recognizes her darling, her little boy, or her little girl - and they fly over to their mothers and kiss them and brush away their tears with their little hands, begging them not to cry, for they feel so happy here....

Next morning, down in the courtyard, porters found the tiny body of a little boy who had hidden behind the piles of kindling wood, and there had frozen to death. They also found his mother. She died even before he had passed away.

Now they are again united in God's Heaven.

And why did I invent such a story, one that conforms so little to an ordinary, reasonable diary - especially a writer's diary? And that, after having promised to write stories pre-eminently about actual events! But the point is that I keep fancying that all this could actually have happened! I mean, the things which happened in the basement and behind the piles of kindling wood. Well, and as regards Christ's Christmas Tree - I really don't know what to tell you, and I don 't know whether or not this could have happened. Being a novelist, I have to invent things.

Frank, A Writer in His Time, 2009, p. 747. The immediately preceding paragraph is also remarkable: ‘The very first issue of the Diary [of a Writer, 1876] contains an extremely touching sketch—“A Little Boy at Christ’s Christmas Party” (Malchik u Christa na Elke)—that could not illustrate more clearly the organic relation between [Dostoevsky’s] journalism and his art. Just a month before, on December 26, 1875, Dostoevsky had taken his daughter to the annual Christmas ball for children at the Artists’ Club in Petersburg, an event famous for the size of the Christmas tree in the ballroom and for the lavishness of its decorations. The next day he paid his visit, already described, to the colony for juvenile delinquents. While going to and fro in the Petersburg streets, and pondering over what to include in his first fascicule, he noticed a little boy begging for alms. These impressions, he wrote Vsevolod Solovyev, solved his problem; he decided to devote a good part of the January [1876] issue “to children— children in general, children with fathers, children without fathers . . . under Christmas trees, without Christmas trees, criminal children.” And so he begins with the Christmas ball and ends with the visit to the colony for delinquents; between them he inserts his fictional sketch.’ The visit to the colony is so relevant, not only to the main theme of this blog, but also to other still little known aspects (s.a. Dostoevsky’s views on “Italianisms” in the Church) that we plan to return to it, God willing. Cf. the recollections of A.F. Koni (in Russian), in the meantime.

For the benefit of our diligent homeschooling readers, parents and children, we also include here the original, as Dostoevsky must have known it (no translation was probably available to him, as per Joseph Frank’s complete 5 tomes bio):

Des fremden Kindes heiliger Christ.

Es läuft ein fremdes Kind

Am Abend vor Weihnachten

Durch eine Stadt geschwind,

Die Lichter zu betrachten,

Die angezündet sind.

Es steht vor jedem Haus

Und sieht die hellen Räume,

Die drinnen schaun heraus,

Die lampenvollen Bäume;

Weh wird’s ihm überaus.

Das Kindlein weint und spricht:

„Ein jedes Kind hat heute

Ein Bäumchen und ein Licht,

Und hat daran seine Freude,

Nur blos ich armes nicht!

An der Geschwister Hand,

Als ich daheim gesessen,

Hat es mir auch gebrannt;

Doch hier bin ich vergessen

In diesem fremden Land.

Läßt mich denn Niemand ein

Und gönnt mir auch ein Fleckchen?

In all’ den Häuserreih’n,

Ist denn für mich kein Eckchen,

Und wär’ es noch so klein?

Läßt mich denn niemand ein?

Ich will ja selbst Nichts haben,

Ich will ja nur am Schein

Der fremden Weihnachtsgaben

Mich laben ganz allein!“

Es klopft an Thür und Thor,

An Fenster und an Laden,

Doch Niemand tritt hervor,

Das Kindlein einzuladen;

Sie haben drin’ kein Ohr.

Ein jeder Vater lenkt

Den Sinn auf seine Kinder;

Die Mutter sie beschenkt,

Denkt sonst nichts mehr noch minder.

An's Kindlein niemand denkt.

„O lieber, heil’ger Christ!

Nicht Mutter und nicht Vater

Hab ich, wenn du’s nicht bist.

O, sei du mein Berather,

Weil man mich hier vergißt!“

Das Kindlein reibt die Hand,

Sie ist von Frost erstarret;

Es kriecht in sein Gewand

Und in dem Gäßlein harret,

Den Blick hinaus gewandt.

Da kommt mit einem Licht

Durch's Gäßlein hergewallet,

Im weißen Kleide schlicht,

Ein ander Kind; - wie schallet

Es lieblich, da es spricht:

„Ich bin der heil’ge Christ,

War auch ein Kind vordessen,

Wie du ein Kindlein bist.

Ich will dich nicht vergessen,

Wenn alles dich vergißt;

Ich bin mit meinem Wort

Bei Allen gleichermaßen;

Ich biete meinen Hort

So gut hier auf den Straßen,

Wie in den Zimmern dort.

Ich will dir deinen Baum,

Fremd Kind, hier lassen schimmern

Auf diesem offnen Raum,

So schön, daß die in Zimmern

So schön sein sollen kaum.“

Da deutet mit der Hand

Christkindlein auf zum Himmel,

Und droben leuchtend stand

Ein Baum voll Sterngewimmel

Vielästig ausgespannt.

So fern und doch so nah,

Wie funkelten die Kerzen!

Wie ward dem Kindlein da,

Dem fremden, still zu Herzen,

Das seinen Christbaum sah!

Es ward ihm wie im Traum;

Da langten hergebogen

Englein herab vom Baum

Zum Kindlein, das sie zogen

Hinauf zum lichten Raum.

Das fremde Kindlein ist

Zur Heimat nun gekehret,

Bei seinem heil’gen Christ;

Und was hier wird bescheeret,

Es dorten leicht vergißt