The Merchant's Story

A famous Nekrasov poem, about a prodigal son, and an unforgettable Dostoevsky story, perhaps inspired by it.

It is difficult to add anything to what follows, except, perhaps, that the Merchant’s Story, from the novel the Adolescent1, first published in Nekrasov’s periodical2, tests, possibly more poignantly that any other story in this collection, the remark that "non-believers find, in the suffering of children, cause for pessimistic embitterment, while believers discover, on the contrary, in the same reality, reasons for reconciliation and universal forgiveness", in the words of Vladika Anthony Khapovitsky3. This is one of our author's key ideas, another being that, deep down, if we can be sincere, we are all believers.

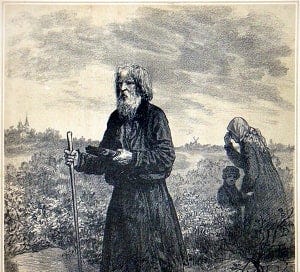

N.A. Nekrasov

VLAS4

In an open-necked peasant overcoat,

And his head bare of all attire,

The old and gray-haired Uncle Vlas

Slowly passes through the town.

With a copper icon on his chest,

He begs for alms for God's own church.

He wears ascetic shackles, humble shoes,

He has a deep scar on his cheek,

And carries a long stick in his hand,

Covered with an iron tip...

It is said that in former times

He was a great sinner. The muzhik

Did not fear God; and his own wife

He beat to death. Not only that,

To horse thieves he gave welcome shelter,

And brigand robbers of all kinds.

From all his poverty-stricken neighbors

He'd buy bread, while in a blackest year

He'd not lend even a copper penny,

But threefold would he fleece the poor!

He took from relatives, from beggars,

Was known to be a vile muzhik;

He had a harsh and austere nature...

But finally the thunder struck!

Vlas is sick, he calls the doctor,

But will help be given a man

Who tore off shirts from needy farmers?

Robbed the beggars of their scrips?

But he's getting ever sicker.

A year has passed, he's still in bed,

And then he swears to build a church,

If he should now be spared from death.

It is said he had a vision,

In delirium he saw

How the world came to an ending,

How the sinners lived in hell,

How the demons did torment them,

How the witches there did sting,

All so black in their appearance,

And their eyes like burning coals.

Crocodiles, snakes, and scorpions

Singed them, cut them, scorched them all,

And the sinners cried in anguish,

Tried to gnaw off rusty chains.

The constant roar of thunder deafened,

A terrible stench did smother them,

And over them with evil laughter

A six-winged tiger circled aloft.

Some on long poles were impaled,

Others licked the burning floor...

There, inscribed on lengthy parchments,

Vlas could read his own grave sins...

Vlas could see the pitch-black darkness

And he proffered his last vow...

Which the Lord did heed – and sent

The sinful soul back to the world.

Vlas gave up all his possessions,

And stayed barefoot and unclothed,

Then went out to make collections

For the building of God's church.

Since that time the peasant wanders,

It will soon be thirty years,

Feeds himself by alms from others,

Strictly keeps the given vow.

All his deepest inner forces

He gives to this godly deed,

As though never savage greed

Was intrinsic to his soul...

Full of inconsolable sorrow,

Dark-complexioned, straight, and tall,

He wanders with unhurried pace

Through cities, villages, and towns.

No way has been too far for him:

He visited the reigning Moscow,

He traveled to the Caspian Sea,

He gazed upon the Neva River.

He goes around with book and icon,

Talks continuously to himself,

And the iron of his shackles

Gently clinks along the way.

He walks all through the freezing winter,

He walks all through the summer heat,

Calling upon baptized Russia

To contribute its earnest gifts, —

And passersby do give and give...

And thus from hard-earned contributions

God's churches spring up all around

Across the face of our native land...

N.A. Nekrasov, 1855

***

F.M. Dostoevsky

The Merchant's Story5

I'll tell you now of a wonderful thing that happened in our town, Afimyevsk. There was a merchant living there, his name was Skotoboynikov, Maxim Ivanovitch, and there was no one richer than he in all the countryside. He built a cotton factory, and he kept some hundreds of hands, and he exalted himself exceedingly. And everything, one may say, was at his beck and call, and even those in authority hindered him in nothing, and the archimandrite thanked him for his zeal: he gave freely of his substance to the monastery, and when the fit came upon him he sighed and groaned over his soul and was troubled not a little over the life to come. A widower he was and childless; of his wife there were tales that he had beaten her from the first year of their marriage, and that from his youth up he had been apt to be too free with his hands. Only all that had happened long ago; he had no desire to enter into the bonds of another marriage. He had a weakness for strong drink, too, and when the time came he would run drunk about the town, naked and shouting; the town was of little account and was full of iniquity. And when the time was ended he was moved to anger, and all that he thought fit was good, and all he bade them do was right. He paid his people according to his pleasure, he brings out his reckoning beads, puts on his spectacles: "How much for you, Foma?" "I've had nothing since Christmas, Maxim Ivanovitch; thirty-nine roubles is my due." "Ough! what a sum of money! That's too much for you! It's more than you're worth altogether; it would not be fitting for you; ten roubles off the beads and you take twenty-nine." And the man says nothing; no one dares open his lips; all are dumb before him.

"I know how much I ought to give him," he says. "It's the only way to deal with the folk here. The folk here are corrupt. But for me they would have perished of hunger, all that are here. The folk here are thieves again. They covet all that they behold, there is no courage in them. They are drunkards too; if you pay a man his money he'll take it to the tavern and will sit in the tavern till he's naked--not a thread on him, he will come out as bare as your hand. They are mean wretches. A man will sit on a stone facing the tavern and begin wailing: 'Oh mother, my dear mother, why did you bring me into the world a hopeless drunkard? Better you had strangled me at birth, a hopeless drunkard like me!' Can you call that a man? That's a beast, not a man. One must first teach him better, and then give him money. I know when to give it him."

That's how Maxim Ivanovitch used to talk of the folk of Afimyevsk. Though he spoke evil of them, yet it was the truth. The folk were froward and unstable.

There lived in the same town another merchant, and he died. He was a young man and light-minded. He came to ruin and lost all his fortune. For the last year he struggled like a fish on the sand, and his life drew near its end. He was on bad terms with Maxim Ivanovitch all the time, and was heavily in debt to him. And he left behind a widow, still young, and five children. And for a young widow to be left alone without a husband, like a swallow without a refuge, is a great ordeal, to say nothing of five little children, and nothing to give them to eat. Their last possession, a wooden house, Maxim Ivanovitch had taken for a debt. She set them all in a row at the church porch, the eldest a boy of seven, and the others all girls, one smaller than another, the biggest of them four, and the youngest babe at the breast. When Mass was over Maxim Ivanovitch came out of church, and all the little ones, all in a row, knelt down before him--she had told them to do this beforehand--and they clasped their little hands before them, and she behind them, with the fifth child in her arms, bowed down to the earth before him in the sight of all the congregation: "Maxim Ivanovitch, have mercy on the orphans! Do not take away their last crust! Do not drive them out of their home!" And all who were present were moved to tears, so well had she taught them. She thought that he would be proud before the people and would forgive the debt, and give back the house to the orphans. But it did not fall out so. Maxim Ivanovitch stood still. "You're a young widow," said he, "you want a husband, you are not weeping over your orphans. Your husband cursed me on his deathbed." And he passed by and did not give up the house. "Why follow their foolishness (that is, connive at it)? If I show her benevolence they'll abuse me more than ever. All that nonsense will be revived and the slander will only be confirmed."

For there was a story that ten years before he had sent to that widow before she was married, and had offered her a great sum of money (she was very beautiful), forgetting that that sin is no less than defiling the temple of God. But he did not succeed then in his evil design. Of such abominations he had committed not a few, both in the town and all over the province, and indeed had gone beyond all bounds in such doings.

The mother wailed with her nurselings. He turned the orphans out of the house, and not from spite only, for, indeed, a man sometimes does not know himself what drives him to carry out his will. Well, people helped her at first and then she went out to work for hire. But there was little to be earned, save at the factory; she scrubs floors, weeds in the garden, heats the bath-house, and she carries the babe in her arms, and the other four run about the streets in their little shirts. When she made them kneel down at the church porch they still had little shoes, and little jackets of a sort, for they were merchant's children but now they began to run barefoot. A child soon gets through its little clothes we know. Well, the children didn't care: so long as there was sunshine they rejoiced, like birds, did not feel their ruin, and their voices were like little bells. The widow thought "the winter will come and what shall I do with you then? If God would only take you to Him before then!" But she had not to wait for the winter. About our parts the children have a cough, the whooping-cough, which goes from one to the other. First of all the baby died, and after her the others fell ill, and all four little girls she buried that autumn one after the other; one of them, it's true, was trampled by the horses in the street. And what do you think? She buried them and she wailed. Though she had cursed them, yet when God took them she was sorry. A mother's heart!

All she had left was the eldest, the boy, and she hung over him trembling. He was weak and tender, with a pretty little face like a girl's, and she took him to the factory to the foreman who was his godfather, and she herself took a place as nurse.

But one day the boy was running in the yard, and Maxim Ivanovitch suddenly drove up with a pair of horses, and he had just been drinking; and the boy came rushing down the steps straight at him, and slipped and stumbled right against him as he was getting out of the droshky, and hit him with both hands in the stomach. He seized the boy by the hair and yelled, "Whose boy is it? A birch! Thrash him before me, this minute." The boy was half-dead with fright. They began thrashing him; he screamed. "So you scream, too, do you? Thrash him till he leaves off screaming." Whether they thrashed him hard or not, he didn't give up screaming till he fainted altogether. Then they left off thrashing him, they were frightened. The boy lay senseless, hardly breathing. They did say afterwards they had not beaten him much, but the boy was terrified. Maxim Ivanovitch was frightened! "Whose boy is he?" he asked. When they told him, "Upon my word! Take him to his mother. Why is he hanging about the factory here?" For two days afterwards he said nothing. Then he asked again: "How's the boy?" And it had gone hard with the boy. He had fallen ill, and lay in the corner at his mother's, and she had given up her job to look after him, and inflammation of the lungs had set in.

"Upon my word!" said Maxim Ivanovitch, "and for so little. It's not as though he were badly beaten. They only gave him a bit of a fright. I've given all the others just as sound a thrashing and never had this nonsense." He expected the mother to come and complain, and in his pride he said nothing. As though that were likely! The mother didn't dare to complain. And then he sent her fifteen roubles from himself, and a doctor; and not because he was afraid, but because he thought better of it. And then soon his time came and he drank for three weeks.

Winter passed, and at the Holy Ascension of Our Lord, Maxim Ivanovitch asks again: "And how's that same boy?" And all the winter he'd been silent and not asked. And they told him, "He's better and living with his mother, and she goes out by the day." And Maxim Ivanovitch went that day to the widow. He didn't go into the house, but called her out to the gate while he sat in his droshky. "See now, honest widow," says he. "I want to be a real benefactor to your son, and to show him the utmost favour. I will take him from here into my house. And if the boy pleases me I'll settle a decent fortune on him; and if I'm completely satisfied with him I may at my death make him the heir of my whole property as though he were my own son, on condition, however, that you do not come to the house except on great holidays. If this suits you, bring the boy to-morrow morning, he can't always be playing knuckle-bones." And saying this, he drove away, leaving the mother dazed. People had overheard and said to her, "When the boy grows up he'll reproach you himself for having deprived him of such good fortune." In the night she cried over him, but in the morning she took the child. And the lad was more dead than alive.

Maxim Ivanovitch dressed him like a little gentleman, and hired a teacher for him, and sat him at his book from that hour forward; and it came to his never leaving him out of his sight, always keeping him with him. The boy could scarcely begin to yawn before he'd shout at him, "Mind your book! Study! I want to make a man of you." And the boy was frail; ever since the time of that beating he'd had a cough. "As though we didn't live well in my house!" said Maxim Ivanovitch, wondering; "at his mother's he used to run barefoot and gnaw crusts; why is he more puny than before?" And the teacher said, "Every boy," says he, "needs to play about, not to be studying all the time; he needs exercise," and he explained it all to him reasonably. Maxim Ivanovitch reflected. "That's true," he said. And that teacher's name was Pyotr Stepanovitch; the Kingdom of Heaven be his! He was almost like a crazy saint, he drank much, too much indeed, and that was the reason he had been turned out of so many places, and he lived in the town on alms one may say, but he was of great intelligence and strong in science. "This is not the place for me," he thought to himself, "I ought to be a professor in the university; here I'm buried in the mud, my very garments loathe me." Maxim Ivanovitch sits and shouts to the child, "Play!" and he scarcely dares to breathe before him. And it came to such a pass that the boy could not hear the sound of his voice without trembling all over. And Maxim Ivanovitch wondered more and more. "He's neither one thing nor the other; I picked him out of the mud, I dressed him in drap de dames with little boots of good material, he has embroidered shirts like a general's son, why has he not grown attached to me? Why is he as dumb as a little wolf?" And though people had long given up being surprised at Maxim Ivanovitch, they began to be surprised at him again--the man was beside himself: he pestered the little child and would never let him alone. "As sure as I'm alive I'll root up his character. His father cursed me on his deathbed after he'd taken the last sacrament. It's his father's character." And yet he didn't once use the birch to him (after that time he was afraid to). He frightened him, that's what he did. He frightened him without a birch.

And something happened. One day, as soon as he'd gone out, the boy left his book and jumped on to a chair. He had thrown his ball on to the top of the sideboard, and now he wanted to get it, and his sleeve caught in a china lamp on the sideboard, the lamp fell to the floor and was smashed to pieces, and the crash was heard all over the house, and it was an expensive thing, made of Saxony china. And Maxim Ivanovitch heard at once, though he was two rooms away, and he yelled. The boy rushed away in terror. He ran out on the verandah, across the garden, and through the back gate on to the river-bank. And there was a boulevard running along the river- bank, there were old willows there, it was a pleasant place. He ran down to the water, people saw, and clasped his hands at the very place where the ferry-boat comes in, but seemed frightened of the water, and stood as though turned to stone. And it's a broad open space, the river is swift there, and boats pass by; on the other side there are shops, a square, a temple of God, shining with golden domes. And just then Mme. Ferzing, the colonel's wife, came hurrying down to the ferry with her little daughter. The daughter, who was also a child of eight, was wearing a little white frock; she looked at the boy and laughed, and she was carrying a little country basket, and in it a hedgehog. "Look, mother," said she, "how the boy is looking at my hedgehog!" "No," said the lady, "he's frightened of something. What are you afraid of, pretty boy?" (All this was told afterwards.) "And what a pretty boy," she said; "and how nicely he's dressed. Whose boy are you?" she asked. And he'd never seen a hedgehog before, he went up and looked, and forgot everything at once--such is childhood! "What is it you have got there?" he asked. "It's a hedgehog," said the little lady, "we've just bought it from a peasant, he found it in the woods." "What's that," he asked, "what is a hedgehog?" and he began laughing and poking it with his finger, and the hedgehog put up its bristles, and the little girl was delighted with the boy. "We'll take it home with us and tame it," she said. "Ach," said he, "do give me your hedgehog!" And he asked her this so pleadingly, and he'd hardly uttered the words, when Maxim Ivanovitch came running down upon him. "Ah, there you are! Hold him!" (He was in such a rage, that he'd run out of the house after him, without a hat.) Then the boy remembered everything, he screamed, and ran to the water, pressed his little fists against his breast, looked up at the sky (they saw it, they saw it!) and leapt into the water. Well, people cried out, and jumped from the ferry, tried to get him out, but the current carried him away. The river was rapid, and when they got him out, the little thing was dead. His chest was weak, he couldn't stand being in the water, his hold on life was weak. And such a thing had never been known in those parts, a little child like that to take its life! What a sin! And what could such a little soul say to our Lord God in the world beyond?

And Maxim Ivanovitch brooded over it ever after. The man became so changed one would hardly have known him. He sorrowed grievously. He tried drinking, and drank heavily, but gave it up--it was no help. He gave up going to the factory too, he would listen to no one. If anyone spoke to him, he would be silent, or wave his hand. So he spent two months, and then he began talking to himself. He would walk about talking to himself. Vaskovo, the little village down the hill, caught fire, and nine houses were burnt; Maxim Ivanovitch drove up to look. The peasants whose cottages were burnt came round him wailing; he promised to help them and gave orders, and then he called his steward again and took it back. "There's no need," said he, "don't give them anything," and he never said why. "God has sent me to be a scorn unto all men," said he, "like some monster, and therefore so be it. Like the wind," said he, "has my fame gone abroad." The archimandrite himself came to him. He was a stern man, the head of the community of the monastery. "What are you doing?" he asked sternly.

"I will tell you." And Maxim Ivanovitch opened the Bible and pointed to the passage:

"Whoso shall offend one of these little ones, which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea." (Math. xviii, 6.)

"Yes," said the archimandrite, "though it was not said directly of this, yet it fits it well. It is sad when a man loses his measure-- the man is lost. And thou hast exalted thyself."

And Maxim Ivanovitch sits as though a stupor had come upon him. The archimandrite gazed upon him.

"Listen," said he, "and remember. It is said: 'the word of a desperate man flies on the wind.' And remember, also, that even the angels of God are not perfect. But perfect and sinless is one only, our Lord Jesus Christ, and Him the angels serve. Moreover, thou didst not will the death of that child, but wast only without wisdom. But this," said he, "is marvellous in my eyes. Thou hast committed many even worse iniquities. Many men thou hast ruined, many thou hast corrupted, many thou hast destroyed, no less than, if thou hadst slain them. And did not his sisters, all the four babes, die almost before thine eyes? Why has this one only confounded thee? For all these in the past thou hast not grieved, I dare say, but hast even forgotten to think of them. Why art thou so horror-stricken for this child for whom thou wast not greatly to blame?"

"I dream at night," Maxim Ivanovitch said.

"And what?"

But he told nothing more. He sat mute. The archimandrite marvelled, but with that he went away. There was no doing anything with him.

And Maxim Ivanovitch sent for the teacher, for Pyotr Stepanovitch; they had not met since that day.

"You remember him?" says he.

"Yes."

"You painted a picture with oil colours, here in the tavern," said he, "and took a copy of the chief priest's portrait. Could you paint me a picture?"

"I can do anything, I have every talent. I can do everything."

"Paint me a very big picture, to cover the whole wall, and paint in it first of all the river, and the slope, and the ferry, and all the people who were there, the colonel's wife, and her daughter and the hedgehog. And paint me the other bank too, so that one can see the church and the square and the shops, and where the cabs stand-- paint it all just as it is. And the boy by the ferry, just above the river, at that very place, and paint him with his two little fists pressed to his little breast. Be sure to do that. And open the heavens above the church on the further side, and let all the angels of heaven be flying to meet him. Can you do it or not?"

"I can do anything."

"I needn't ask a dauber like you. I might send for the finest painter in Moscow, or even from London itself, but you remember his face. If it's not like, or little like, I'll only give you fifty roubles. But if it's just like, I'll give you two hundred. You remember his eyes were blue...And it must be made a very, very big picture."

It was prepared. Pyotr Stepanovitch began painting and then he suddenly went and said:

"No, it can't be painted like that."

"Why so?"

"Because that sin, suicide, is the greatest of all sins. And would the angels come to meet him after such a sin?"

"But he was a babe, he was not responsible."

"No, he was not a babe, he was a youth. He was eight years old when it happened. He was bound to render some account."

Maxim Ivanovitch was more terror-stricken than ever.

"But I tell you what, I've thought something," said Pyotr Stepanovitch, "we won't open the heaven, and there's no need to paint the angels, but I'll let a beam of light, one bright ray of light, come down from heaven as though to meet him. It's all the same as long as there's something."

So he painted the ray. I saw that picture myself afterwards, and that very ray of light, and the river. It stretched right across the wall, all blue, and the sweet boy was there, both little hands pressed to his breast, and the little lady, and the hedgehog, he put it all in. Only Maxim Ivanovitch showed no one the picture at the time, but locked it up in his room, away from all eyes; and when the people trooped from all over the town to see it, he bade them drive every one away. There was a great talk about it. Pyotr Stepanovitch seemed as though he were beside himself. "I can do anything now," said he. "I've only to set up in St. Petersburg at the court." He was a very polite man, but he liked boasting beyond all measure. And his fate overtook him; when he received the full two hundred roubles, he began drinking at once, and showed his money to every one, bragging of it, and he was murdered at night, when he was drunk, and his money stolen by a workman with whom he was drinking, and it all became known in the morning.

And it all ended so that even now they remember it everywhere there. Maxim Ivanovitch suddenly drives up to the same widow. She lodged at the edge of the town in a working-woman's hut; he stood before her and bowed down to the ground. And she had been ill ever since that time and could scarcely move.

"Good mother," he wailed, "honest widow, marry me, monster as I am. Let me live again!"

She looks at him more dead than alive.

"I want us to have another boy," said he. "And if he is born, it will mean that that boy has forgiven us both, both you and me. For so the boy has bidden me."

She saw the man was out of his mind, and in a frenzy, but she could not refrain.

"That's all nonsense," she answered him, "and only cowardice. Through the same cowardice I have lost all my children. I cannot bear the sight of you before me, let alone accepting such an everlasting torture."

Maxim Ivanovitch drove off, but he did not give in. The whole town was agog at such a marvel. Maxim Ivanovitch sent match-makers to her. He sent for two of his aunts, working women in the chief town of the province. Aunts they were not, but kinsfolk of some sort, decent people. They began trying to turn her, they kept persuading her and would not leave the cottage. He sent her merchants' wives of the town too, and the wife of the head priest of the cathedral, and the wives of officials; she was besieged by the whole town, and she got really sick of it.

"If my orphans had been living," she said, "but why should I now? Am I to be guilty of such a sin against my children?"

The archimandrite, too, tried to persuade her. He breathed into her ear:

"You will make a new man of him."

She was horrified, and people wondered at her.

"How can you refuse such a piece of luck?"

And this was how he overcame her in the end.

"Anyway he was a suicide," he said, "and not a babe, but a youth, and owing to his years he could not have been admitted to the Holy Communion, and so he must have been bound to give at least some account. If you enter into matrimony with me, I'll make you a solemn promise, I'll build a church of God to the eternal memory of his soul."

She could not stand out against that, and consented. So they were married.

And all were in amazement. They lived from the very first day in great and unfeigned harmony, jealously guarding their marriage vow, and like one soul in two bodies. She conceived that winter, and they began visiting the churches, and fearing the wrath of God. They stayed in three monasteries, and consulted prophecy. He built the promised church, and also a hospital, and almshouses in the town. He founded an endowment for widows and orphans. And he remembered all whom he had injured, and desired to make them restitution; he began to give away money without stint, so that his wife and the archimandrite even had to restrain him; "for that is enough," they said. Maxim Ivanovitch listened to them. "I cheated Foma of his wages that time," said he. So they paid that back to Foma. And Foma was moved even to tears. "As it is I'm content..." says he, "you've given me so much without that." It touched every one's heart in fact, and it shows it's true what they say that a living man will be a good example. And the people are good- hearted there.

His wife began to manage the factory herself, and so well that she's remembered to this day. He did not give up drinking, but she looked after him at those times, and began to nurse him. His language became more decorous, and even his voice changed. He became merciful beyond all wont, even to animals. If he saw from the window a peasant shamelessly beating his horse on the head, he would send out at once, and buy the horse at double its value. And he received the gift of tears. If any one talked to him he melted into tears. When her time had come, God answered their prayers at last, and sent them a son, and for the first time Maxim Ivanovitch became glad; he gave alms freely, and forgave many debts, and invited the whole town to the christening. And next day he was black as night. His wife saw that something was wrong with him, and held up to him the new-born babe.

"The boy has forgiven us," she said; "he has accepted our prayers and our tears for him."

And it must be said they had neither of them said one word on that subject for the whole year, they had kept it from each other in their hearts. And Maxim Ivanovitch looked at her, black as night. "Wait a bit," said he, "consider, for a whole year he has not come to me, but last night he came in my dream."

"I was struck to the heart with terror when I heard those strange words," she said afterwards.

The boy had not come to him in his dream for nothing. Scarcely had Maxim Ivanovitch said this, when something happened to the new-born babe, it suddenly fell ill. And the child was ill for eight days; they prayed unceasingly and sent for doctors, and sent for the very best doctor in Moscow by train. The doctor came, and he flew into a rage.

"I'm the foremost doctor," said he, "all Moscow is awaiting me."

He prescribed a drop, and hurried away again. He took eight hundred roubles. And the baby died in the evening.

And what after that? Maxim Ivanovitch settled all his property on his beloved wife, gave up all his money and all his papers to her, doing it all in due form according to law, then he stood before her and bowed down to the earth.

"Let me go, my priceless spouse, save my soul while it is still possible. If I spend the time without profit to my soul, I shall not return. I have been hard and cruel, and laid heavy burdens upon men, but I believe that for the woes and wanderings that lie before me, God will not leave me without requital, seeing that to leave all this is no little cross and no little woe."

And his wife heard him with many tears.

"You are all I have now upon the earth, and to whom am I left?" said she, "I have laid up affection in my heart for you this year."

And every one in the town counselled him against it and besought him; and thought to hold him back by force. But he would not listen to them, and he went away in secret by night, and was not seen again. And the tale is that he perseveres in pilgrimage and in patience to this day, and visits his dear wife once a year.

“[I]n its flaws and virtues the most Dostoevskian of Dostoevsky’s novels”, according to Victor Terras.

Notes of the Fatherland (1875). There is reason to believe that Nekrasov understood the value of the novel. To quote Richard Pevear’s Introduction to Larissa Volokhonsky's translation (2003): ‘In April 1874, when Dostoevsky offered Mikhail Katkov, editor of The Russian Messenger, the plan for a new novel, Katkov turned it down. (Only later did Dostoevsky learn that Katkov already had a big novel coming in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, for which he was paying twice as much as Dostoevsky had asked.) Then, quite unexpectedly, Nekrasov came to him and offered to take the novel for Notes of the Fatherland. Dostoevsky’s wife wrote in her memoirs: “My husband was very glad to renew friendly relations with Nekrasov, whose talent he rated very highly.” Though she added that “Fyodor Mikhailovich could in no case give up his fundamental convictions.” He remained somewhat skeptical of this sudden interest from his former enemies, and vowed that he “would not concede a line to their [liberal-radical] tendency,” but in the end Nekrasov’s enthusiastic response to the first parts won him over. “All night I sat and read, I was so captivated,” the poet told him. “And what freshness, my dear fellow, what freshness you have! . . . Such freshness no longer exists in our age, and not one writer has it.” Thirty years before, Nekrasov had greeted Dostoevsky’s first novel, Poor Folk, with the same enthusiasm and had been largely responsible for his initial success. This closing of the circle must have moved Dostoevsky deeply.’ Quite interestingly, Pevear continues:

‘In fact, Nekrasov even has a certain presence in The Adolescent. The figure of Makar Dolgoruky is based in part on the description of the old peasant wanderer in Nekrasov’s poem “Vlas,” as Dostoevsky signals by having Versilov quote a line from it when he first describes Makar to Arkady. Dostoevsky had written an admiring article on “Vlas” in 1873, a year before he began work on the novel. But there is another more hidden presence. Towards the end of the tribute he wrote in 1877 on the occasion of Nekrasov’s death, he speaks of a dark side to the poet’s life, which he foretold in one of his earliest poems. And he quotes three stanzas describing the young provincial’s arrival in the capital – “The lights of evening lighting up, / There was wind and soaking rain / . . . on my shoulders a wretched sheepskin, / In my pocket fifteen groats” – and ending: “No money, no rank, no family,/ Short of stature and funny looking,/ Forty years have passed since then –/ In my pocket I’ve got a million. This was the adolescent poet’s dream of power. “Money,” Dostoevsky writes, “that was Nekrasov’s demon! . . . His was a thirst for a gloomy, sullen, segregated security with a view to dependence on no one.” This soul that sympathized with all of suffering Russia also had its “Rothschild idea” and its underground.’

One only wishes that Pevear would have also compared Vlas to merchant Skotoboinikov. For, they rather obviously shared both a more inner “dark side”, and the repentance for it. As for that other hero of the novel mentioned above, the humble peasant pilgrim and storyteller Makar (who tells the story of the merchant), while “outer” resemblances with Vlas exist, and are mentioned in the novel, by a somewhat superficial character, he actually seems to us “innerly” closer to Peasant Marey, or even to Prince Myshkin (see the story of Marie, forthcoming). I.e., to an alter-ego of the Marey-Myshkin side of the author himself. An exploration would also be needed, therefore, in order to more clearly assess the depth of Dostoevsky’s “hidden” message to his old friend, Nekrasov. But our readers will undoubtedly take the additional steps themselves, starting from Pevear’s remarks above. Also cf. the printed Romanian version of Dostoevsky for Parents and Children (RDPC).

Translation by Dr. Ludmila Koehler. An idea also illustrated, as the Metropolitan points out, by the story of Iliusha, forthcoming in DPC, from the conclusion of the Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky’s final masterpiece.