A Second Foreword to Dostoevsky for Parents and Children (1897)

A long overdue posting - and we dare hope, a substantial treat (with apologies to our deeply cherished readers, for not being able to devote more time to the DPC project, that is very dear to us)

Our selection of edifying short stories and excerpts is based on the first (1883) and last (1897) of the three original anthologies “for children” supervised by Anna Grigorievna Dostoevskaya (with the editorial assistance of trusted and eminent scholars), that were her three increasingly successful ways of completing a project inherited from her beloved husband, F.M. Dostoevsky (+1881). Her second original anthology (1887) was left out here, as it comprises only complete, or larger selections from longer pieces: “Mr. Prokharchin”, Netochka Nezvanova, Poor People, and Notes from the House of the Dead. We felt that these could, nowadays, safely be left at the discretion of those interested, among the readers of the amazing collection of shorter pieces from the other two collections. By comparison, the latter seemed still neglected, not easily found in one place by their intended readership, and thus, calling for attention. Here is the editor’s Foreword, followed by a heartwarming biographical sketch of the author’s life, by the same A. V. Kruglov, Anna Dostoevskaya’s collaborator for the 1897 “children’s book1:”

DOSTOYEVSKY

For school-age children

__________________________

Edited by A.V. KRUGLOV

__________________________

With a biographical sketch,

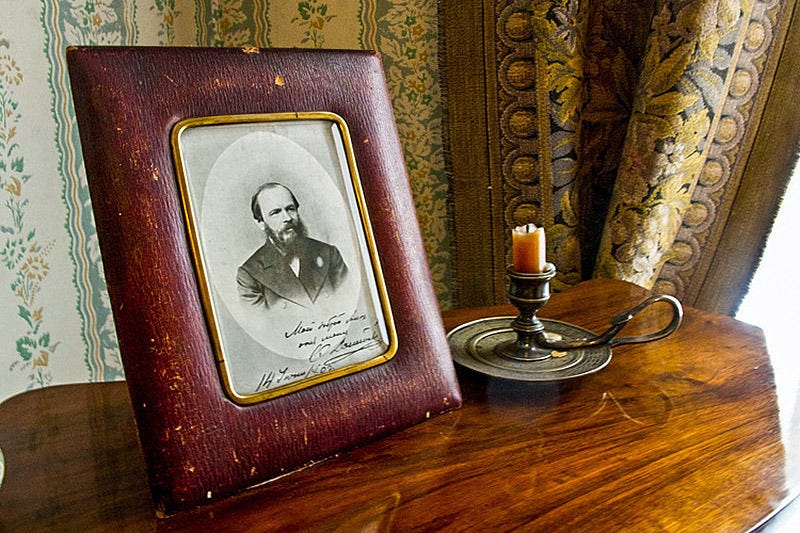

a portrait of F.M. Dostoyevsky, and photographs of his home

and the school named after him.

Saint Petersburg.

Printing Press of the Panteleyev Brothers, 16 Vereyskaya Street.

1897.

FOREWORD

One could make do without a foreword, if it were not for the thought that people who have become accustomed to thinking in stereotypes will probably comment: “Dostoyevsky is not for children.” Someone even stated this in print, when the anthology For Russian Children, compiled by Professor O.F. Miller, was published. Naturally the entire Dostoyevsky, as a whole, is not for children. But there is not a single writer who could be used in his entirety for the library of young readers. No wonder that there exists special juvenile literature. But it would lose a great deal, if everything that could be taken from the best literary artists were to be excluded from it. It is inexcusable for children to remain unacquainted with the works of a great writer until they are able to read him in his entirety. Why deprive the young reader of what is most precious in the sphere of artistic creation – the possibility of becoming acquainted with life in the renditions of the greatest masters of literary art! It is only necessary that such acquaintance not mar the true appreciation of great artists. One can refrain from showing all images, but everything should remain in the original, in order to retain its artistry, which suffers from any alteration.

But I will be told that a grim image will not become bright in such a case. First of all, the impression of it will undoubtedly soften when its harshest aspect is discarded, which is often harsh simply in its totality. Secondly, every writer and, consequently, Dostoyevsky as well, does not have only grim images. Thirdly, the question of how to understand the word “grim” should first be clarified, not to mention the fact that the young reader should not be exclusively provided with only the bright manifestations of life, just as this life should not be drawn exclusively in gloomy colors. Naturally children should not be acquainted only with Dostoyevsky. But the choice is plentiful, and Dostoyevsky is only one of a number of Russian classics. His colors are vivid, his images are true, and they should not be passed by. I believe in that Dostoyevsky's “grimness” (and I say this from experience) is not dangerous, but on the contrary, it is benevolent, and that many of his pages are comprehensible to older children (from the age of 12 or so), naturally those who are more or less mature. While reading Dostoyevsky, children will rarely laugh (although sometimes they will), but does every book have to arouse laughter? Laughter is salutary, but it does not hurt for a child to sometimes cry with those good holy tears that are as beneficial for the soul as warm spring rain for the field. It is not these tears that make children nervous – believe me, not these! There are, naturally, sick nervous children, who cannot bear anything that is sad. But these are sick children. Perhaps they are like that because life is cruel and full of fathers and mothers who are incapable of crying with good tears, but tend towards wretched tearfulness. Being a great artist, Dostoyevsky does not have any falsehood in his depiction of life and man, and the writer's voice sounds authoritatively, while his colors are vivid. There is a great deal of sorrow in life, children see and experience it, so how will you conceal it from them? Let them make sense of it, understand and feel it with the help of the one who loved all the “insulted and humiliated.” Tears will fall on the book, yet they will not be tears of despair and rancor, but of commiseration, compassion, and love. These tears will not poison hearts, but will touch the best strings of the soul and will encourage stronger love. Whoever causes children to feel love is undoubtedly beneficial for them. There is no need for aimless gloom, and there is none of it in Dostoyevsky. Take the story of Ilyusha2: it is sad. But, by God, how much light and warmth there is here, how much love that will run through children's hearts as a life-giving stream. And whatever produces such an effect is not grim in a poisonous sense. A child with a wooden attitude towards life cannot be considered as being ideal. If one shows only bright things to a child, one can give him a false understanding of life, leave him unprepared for it, fail to teach him to understand the sorrows of others, and rear him as a dry egoist, and thus, consequently, a coward in the battle of life. Besides, no matter how much you try to eliminate all grimness from a book, you cannot eliminate it completely from life. I agree that continuous grief can crush a person. But that is why I say that the reading of Dostoyevsky should alternate with the reading of other writers.

This anthology opens with a brief memoir – “Marey the Peasant.” This is a touching image, concise, vivid. The sympathetic Marey is depicted fully in just a few strokes. The sketch “A Boy at Christ's Christmas Tree” contains sadness, but the sketch provokes serious thoughts that are quite salutary. “The Centenarian” is a sketch from life, far from gloomy, depicting an old woman who is extraordinarily charming in her simplicity and sober innocence. “Foma Danilov3” is just a short piece, but it would be unforgivable to omit it from a children's book, especially in our times. Dostoyevsky knew what he was doing when he brought this newspaper article to the attention of subscribers to the Writer's Diary. I understand why this article was taken up by O.F, Miller as well. I deliberately placed it in the beginning of the book, right after “Marey” and “The Centenarian.” The article not only directs the child's thoughts to an issue that is frivolously ignored by many, but also wonderfully illuminates the soul of a simple person, who is course, ignorant, inclined towards great sins, but also capable of acting in a way “in which we, sirs, would scarcely act.” It is necessary to show Foma's “heroism” to the young reader in a proper light. Those who fear negative characters in children's literature would on no account include an “honest thief.”

But I am not afraid of those negative characters and images that teach children positive goodness, teach them to understand unfortunate others. Besides, there is a positive character here as well. I read this story in a family where there were four listeners (the oldest was 15). They understood the author's idea4. Both excerpts from the novel The Teenager5 are undoubtedly beneficial in an educational sense. The first one will especially touch the child's heart. The second one is comprehensible to older children, who will understand the merchant's anguish. But the boy's sorrow was clearly felt even by an 11-year-old girl, who read the story aloud in my presence.

I included an excerpt from Poor People – Varenka's account of her childhood6. Here everything appears to be sad, but is also speaks to the heart. Varya, the student Pokrovskiy, and his father are depicted wonderfully, as is Anna Fedorovna in a few strokes. The young reader will experience all the agitations of the “main characters,” primarily Varya, with trepidation. When the scene of the purchase of a gift for Pokrovskiy, and all the following ones, were read in a school, there was total silence on the part of all the children (there were 20). They were happy for Varya, who found the works of Pushkin at a flea market – this could be seen on their faces. Pokrovskiy's father aroused friendly loving laughter in some of them. But he was understood. One girl exclaimed: “Oh, I am especially sorry for him!” Pokrovskiy's death and his funeral had a strong effect on the listeners. Many of them cried (especially the girls). But these tears are not to be feared, if education is conducted in a sensible manner. Children see such tears in life as well.

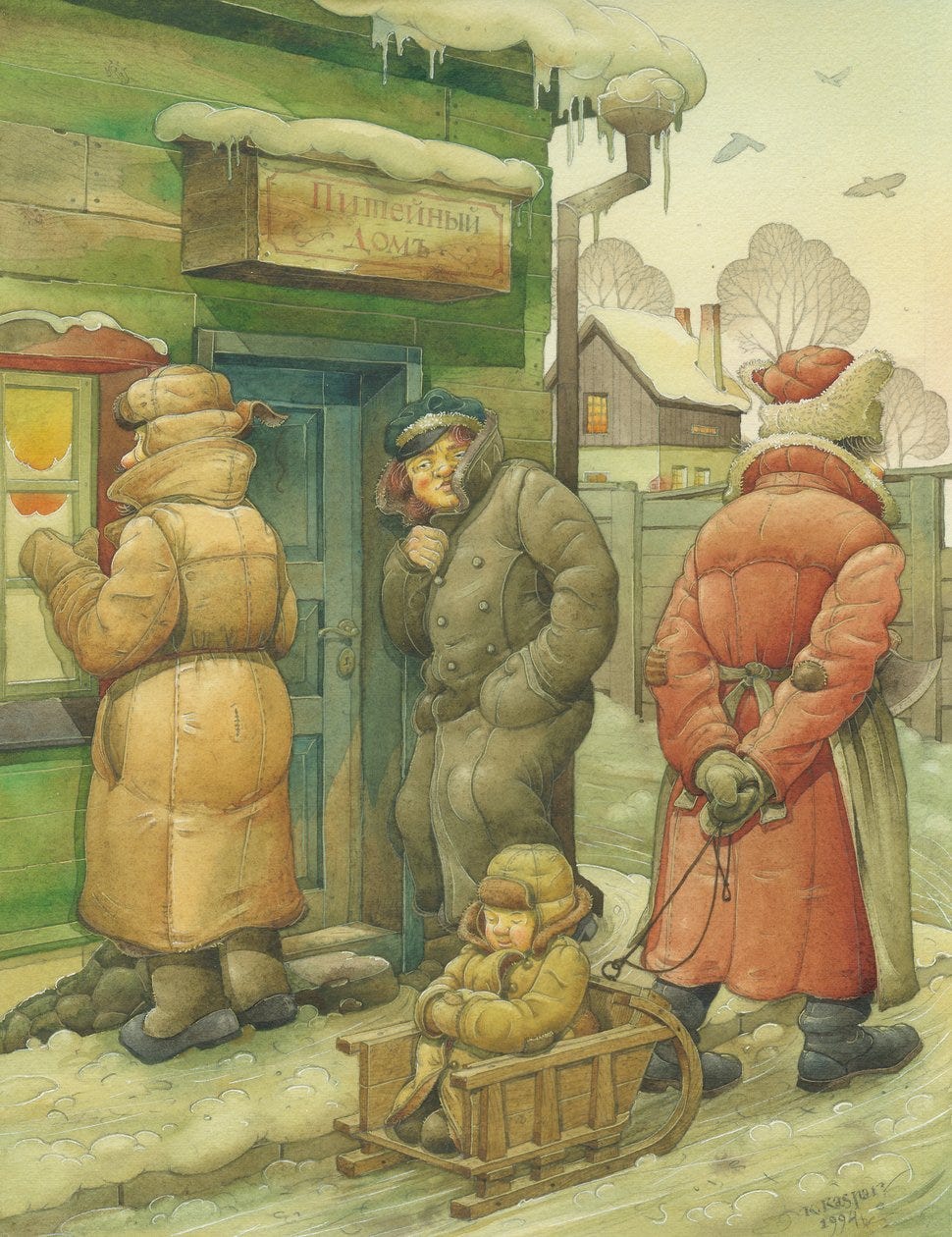

Notes from the House of the Dead, in the form in which they are presented to young readers7, do not give an impression of something crushing or desperately joyless, even though they evoke sadness. There are a number of bright points even in sad images, if one does not limit oneself solely to externals. Such are the personages of Alley and Nurra, images of the holiday, theatrical productions, sketches of animals. One can feel humaneness in places where it could not be expected. One does not even have to mention the usefulness of getting to know what the life of prisoners is like – that is quite obvious.

As regards Netochka Nezvanova8, at first I wanted to include only the story of her life in the prince's house. But after pondering the content of the first part, I decided to likewise include the account of the ordeals of Neta's stepfather and of her life in her own family. This is necessary to understand the subsequent content and to clarify Netochka's character. Moreover, Yefimov is interesting in his own right, as a typical representative of Russian unsuccessful artistic natures, who perish due to their characteristics. In many pages (for example, after the concert), Dostoyevsky's writing attains amazing perfection. Yefimov stands before the reader as a living person, and his every action, every movement of the soul is explained with a skill that can be encountered only in artistic geniuses. And children understand the writer. I should say here that I tested this continuously on children, and also asked my friends who deal with children to do the same. The story about Yefimov was read among children at a party. Of the 14 children (three girls and eleven boys), only one 12-year-old girl did not like this story and did not understand it. Truth to say, I was the one to read it, and I directed the young listeners' thoughts to some extent. So what prevents adults from taking on the role of instructors? What prevents many of them is laziness and the desire to engage in their own amusements. But what can give greater enjoyment than conversation with children, whose thoughts are already affected by the book?

All the scenes from The Brothers Karamazov9 I daringly cite as being bright and comforting, despite their sad content and the grief permeating many of the pages. The meek character of Alyosha, the majestic image of the righteous Zosima, his reminiscences and teachings, the story of Ilyusha – all of this is infused with such internal light, is full of such benign warmth, that it is strange to speak of a depressing impression. There is no doubt that whoever is able to keenly feel the story of Ilyusha will never become the “murderer” of another Ilyusha. One can see sorrow, and also bring sorrow to others. But whoever is able to understand the suffering of another, and whoever allows his heart to be burned by the sufferings and tears of others, such a one will never be able to cause distress and tears in the world himself.

In this manner the “writer who is not for children” gives a lot to children, and all of it is quite precious. I have made excerpts, sometimes uniting portions taken from different parts of the piece into one, but I have not changed a single stroke written by the great writer, nor have I made any alterations, believing all infringements to be a reprehensible impertinence. I could not take everything from Dostroyevsky10, but everything that I took belongs to him, is presented in his words, is depicted with his brush. And I am certain that young readers will come to love the late writer and, maturing to the extent of understanding all of him, will want to read his writings in their entirety, in order to enjoy his images in all their fullness and breadth.

I am not writing this foreword for those for whom this anthology is intended, but for their parents and teachers, and for all those who think that “Dostoyevsky is not for children.” To these latter I suggest that they begin reading the anthology straight from the small biographical sketch I have composed, in order to become acquainted with the life and personality of Fedor Mikhaylovich Dostroyevsky. Full acquaintance with him and his work will naturally become possible for my readers only when the entire Dostoyevsky becomes accessible to them.

***

Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoyevsky

It is impossible for you not to know this name, even if you haven't read any of Dostoyevsky's writings. The entire educated Russia knows him. His literary works are available in every provincial library. And not only his books, but even his portrait you may have seen perhaps in the office of your father, brother, or acquaintance.

You will naturally be interested in the author's personality and life as well. One can become thoroughly acquainted with his personality and life only after becoming completely acquainted with his writings. But for the time being this is still impossible for you, and if the late writer's friend says that he “does not have enough courage” to call his sketch of Dostoyevsky's life a “real” biography, then all the more will I not call my jottings so either. I simply wish to tell you a little about the late writer, relate some features of his life, and touch upon several moments in his life and work, in order to illuminate at least to some extent the spiritual image of the one whose lines will excite your heart and arouse various thoughts in your mind. And afterwards, if you have time – you will read all of Dostoyevsky's works, read them not once, but many times, and you will become thoroughly acquainted with his personality and his life, so rich in inner content...

And now – some pages from this extensive and engaging biography.

Dostoyevsky was a native Muscovite. He was born on 30 October 1821, in a wing of the Mariinsky Hospital, in which Fyodor Mikhaylovich's father, Mikhail Andreyevich Dostoyevsky, worked as a physician. Dostoyevsky's earliest recollection was of how his nanny once brought him at the age of 3 into the living room, made him kneel before the icon, and read the following bedtime prayers: “I place my entire hope in Thee, O Lord. O Mother of God, keep me under Thy protection.” This recollection became engraved in his memory, he said this prayer his entire life, and read it as he blessed his children at bedtime.

In his own words, Dostoyevsky received a strict upbringing. Mikhail Andreyevich loved his children (Dostoyevsky had several brothers and sisters; the eldest brother, Mikhail, is likewise somewhat known in literature), willingly talked with them about everything that could educate them, gave them the freedom to express their thoughts, but in general he was strict, and the nanny often had to conceal the children's pranks from him. Dostoyevsky used to say about his father: “He was like real fire.” And, in fact, he was very quick and heated in his conversations. Having read a lot about savages, the very young Dostoyevsky (who began to learn to read and write when he was five) liked to play at “savages.” According to the youngest brother Andrey, the game consisted of their choosing a dense place in the grove, putting up a tent there, and making it the main site of wild tribes.

Undressing themselves, they painted their bodies with paints like tattoos, made head and waist ornaments out of leaves and colored goose quills, and armed with self-made bows, engaged in imaginary attacks. Dostoyevsky was the leader of the tribe. “I remember once,” says the youngest brother Andrey,” in dry and fair weather, our mother, wanting to extend our pleasure, ordered lunch to be taken to the “savages” outside, in special dishes, and for the food to be placed under the bush. We ate without knives and forks, as is customary with savages. But when we wanted to spend the night in a “savage state,” this we were not allowed.”

Besides this game, Dostoyevsky also liked to play at Robinson Crusoe. All of this took place during their stay at the estate, which consisted of two small villages which Mikhail Andreyevich had bought in 1831. In the city, of course, there was no such freedom, and the children willingly traveled to the village. They loved to run in the fields, watch the peasants at work, and talk with them. Little Fedya was especially well-regarded by the villagers. He became close friends with them. He would either ask to lead a horse with a harrow, or drive a horse in a plow, or he would start talking with the peasants. But his greatest pleasure was to fulfill someone's tasking or render a service. Once a peasant woman, who went out into the field to reap, brought her child with her, since there was no one with whom to leave him at home. Somehow she accidentally spilled a jug with water. The little Dostoyevsky joyously ran off to the village, a mile-and-a-half away, and brought back a jug of water. Even then he already loved the poor people, who repaid him for his love with their love. This anthology opens with a small story, in which Dostoyevsky recollects one of his childhood adventures in the village. This story perfectly describes the peasant Marey's attitude towards the young lordling.

Prior to buying the estate, Dostoyevsky's parents traveled every summer to the Trinity-Sergius Lavra. They spent several days at the Lavra, attending all church services. Perhaps in these early years Dostoyevsky was already enthralled by the poetry of church hymns, and a spark of faith fell into his tender child's soul, which subsequently burned as a bright flame within him, taught him patience and love, and made him a true Russian and an active son of the Orthodox Church. Zosimas are rare, but they can still be encountered, and perhaps the words of some Zosima burned through the child's heart then. These childhood recollections are very strong, and nothing can completely destroy them and erase them from the memory. The first book that Dostoyevsky read was the Sacred History of the Old and New Testament. Later, when the adult Dostoyevsky found this book, he delightedly let his brother know about his find. The deacon who taught the Law of God had a great influence upon the boy. This man, who was extraordinarily eloquent, not only fascinated children and adults with stories from the Sacred History, but also touched their hearts. When you read about the Elder Zosima in this anthology, you will understand why such fervent and wonderful lines on the Sacred History flowed from under Dostoyevsky's pen.

Prior to entering a boarding school with secondary-level courses, Dostoyevsky and his brothers studied at home, and afterwards with a certain Drashusov, to whose home they traveled daily. Mikhail Andreyevich himself undertook to teach his sons Latin, and conducted studies with them in the evenings. The boys were afraid of these lessons, because their father was strict, demanding, and hot-tempered. However, he never punished his children, and the entire threat was limited to shouting: he would call his sons lazybones and would break off the lessons. But even this was already a punishment for the children. Mikhail Andreyevich did not tolerate caning, and for this reason he did not send the boys to a secondary school, but placed them in a private boarding school run by a certain Chermak, who treated the children as thought he were their own father and paid heed to all their smallest needs. He always dined at the same table with his pupils.

On Sundays and holidays the Dostoyevsky boys came home and shared their impressions with their parents, telling them about everything that seemed interesting to them. The boys always spoke with great delight about the Russian language teacher, who taught his subject excellently and had great influence on the students. There was complete openness between the children and the parents. Mikhail Andreyevich did not like to lecture his children; when told about the pranks which took place at the boarding school, the father only muttered: “What a scamp... what a rogue!,” but not once did he say: “Make sure that you do not behave in the same way!” By this he wanted to show that he could not even expect anything like that from them. After lunch the children sat down to do some reading. Dostoyevsky and his brothers read a great deal and most often within the circle of their parents. Sometimes the parents themselves read aloud. Dostoyevsky most of all liked descriptions of travels and historical writings. He read Walter Scott and Narezhnyy. Karamzin's History of Russia was his much-loved book. Both brothers were united in admiring Pushkin; they knew many of the great poet's poems by heart. Mikhail Mikhaylovich even scribbled some poems himself at that time.

The year of 1837 was a difficult year for the Dostoyevskys. They lost their mother, who passed away on February 27. Mikhail Andreyevich set up a tombstone on his wife's grave and left it to his older sons to make an inscription on the tombstone. They both decided that only the first name, last name, and dates of birth and death should be inscribed. For the back side of the tombstone they chose an inscription from Karamzin: “Rest, dear remains, until the joyous morning!” That same year Pushkin died as well. Dostoyevsky's love for him can be seen from the fact that he said to his brother: “If we were not in family mourning, I would have asked Father permission to wear mourning for Pushkin.”

Soon after his mother's death, Dostoyevsky and his brother were driven to St. Petersburg, where he entered the School of Engineering, while his brother, who was for some reason found to be sick (although he was stronger than Dostoyevsky), went off to Revel and became a member of an engineering team there. At that time the School of Engineering was greatly distinguished among other colleges. It now prides itself on having had such students as Totleben, Kaufman, Radetsky, Sechenov, Grigorovich, Trutovsky, and Dostoyevsky. While at school, Dostoyevsky, assiduously engaging in his studies, continued to read a lot and to become acquainted with Homer, Schiller, and Balzac. Interesting information about the time of Dostoyevsky's stay at the school is provided by one of the officers who had served at the institution, the now Lieutenant General A.I. Savelyev. He tells of Dostoyevsky's friendship with a certain Berezhitsky and of how both of them avoided games and did not attend dance classes, but used their free time for reading and conversation. In general, Dostoyevsky stayed away from his superiors and older classmates, and was especially kind to those who, due to their status at the school, had no voice or protection. Even then “the humiliated and the insulted” attracted his attention. He uncomplainingly submitted to all the demands of military service, although he had absolutely no vocation for it. But at the same time he was one of those people who do not put up with the actions of others, if they do not agree with their own views.

The “firebrand,” as Dostoyevsky was considered to be in childhood, noticeably changed in the Engineering School. He was frequently visited by very sad and gloomy thoughts; he was never seen to be cheery and idle, attests A.I. Savelyev. According to him, Dostoyevsky's favorite place for studies was the window embrasure in the corner bedroom that faced the Fontanka Street. Here Dostoyevsky sat and studied. “It often happened that he did not notice anything that took place around him; Dostoyevsky put away his books and notebooks only when the drummer, who passed through the bedrooms and beat the drum to indicate sunset time, forced him to interrupt his studies. But Dostoyevsky often got up at night and again sat down to write.” To what did the young Dostoyevsky dedicate the night hours? Savelyev says that it was already then that Dostoyevsky began to write his first novel, The Poor Folk (an excerpt from it is included in the present anthology). It cannot be affirmed that Savelyev is not mistaken, because Dostoyevsky's own words about the time of his writing “The Poor Folk” differ somewhat from Savelyev's statement. Perhaps that was an initial draft of the novel, which was later destroyed by Dostoyevsky. But it is correct to say that Dostoyevsky already began to write at school, absorbed in the authors he had read and following the example of the poet Shidlovsky, with whom he was friends. But that was just the external stimulus. Dostoyevsky had much to say, as shown by his novel The Poor Folk, which straightaway brought fame to the young author. The dramas he had written earlier were never printed anywhere and did not reach us.

After completing a full course of studies in the upper-level officer class, in 1842 Dostoyevsky entered service in the St. Petersburg Engineering Team. Now he engaged in literary efforts with even greater enthusiasm. He took a long time to write The Poor Folk, correcting and rewriting it several times. In the end he was satisfied with it. He wrote to his brother Mikhail on 24 March 1845: “I am greatly satisfied with my novel. It is an exact and streamlined piece.” He hoped that the novel would save him from indebtedness and would bring in good money. Not knowing how to manage his affairs and being too trusting of people, Dostoyevsky became entangled in money matters and was greatly in need. The young author also suffered great anguish because he was unable to decide whether to have the novel published as a separate book or to first have it appear in a magazine. Dostoyevsky's friend Grigorovich (now a well-known writer, but at that time not having yet written anything) acquainted him with Nekrasov, whose poems you naturally know. Nekrasov decided to publish an anthology. However, Dostoyevsky, though certain of the merits of his work, was embarrassed to give his manuscript to Nekrasov. At that time V.G. Belinsky was of great consequence among critics, and the young writer was afraid of him. “He will ridicule my Poor Folks, thought Dostoyevsky, who had written the novel practically with tears. In the evening of the day he gave his manuscript to Nekrasov, Dostoyevsky went to visit one of his friends and returned home at around 4:00 in the morning. It was a wonderful white night outside, as occurs in St. Petersburg in the spring. Having no wish to sleep, Dostoyevsky sat at an open window and fell to thinking. Suddenly the bell in the hallway rang loudly. It was Grigorovich and Nekrasov. They excitedly fell upon Dostoyevsky and embraced him. Dostoyevsky himself described the moment in the following manner: “The day before, they had returned home in the evening, took my manuscript and began to read it, to try it out. But having read ten pages, they decided to read more, and then, without stopping, they sat through the whole night until the morning, reading aloud and taking turns at it. “He was reading about the death of the student, – Grigorovich would tell me afterwards, – and suddenly I saw that in the part where the father runs behind the casket, Nekrasov's voice faltered, once, twice, then he could no longer stand it, he thumped the manuscript with his palm and said: 'Oh, let him go blow!' That was about you!” And when they finished, they decided to go to see me immediately. “What does it matter if he's sleeping – we will wake him up, this is way beyond sleep.” And they stayed with me for half-an-hour, and we spoke of God knows how many things, understanding each other with a single word, exclaiming and hurrying all the while, and we spoke of poetry, of truth, of Gogol, quoting from his “The Inspector General” and Dead Souls, but mainly of Belinsky. “I will take your story to him today, and you will see, he is such a person, such a person!... When you become acquainted with him, you will see what a soul he is!” Nekrasov said exuberantly, shaking my shoulders with both hands. “And now, go to sleep – we are going away, and tomorrow you will come to see us.” As though I could go to sleep after them! What rapture, what success! And most precious of all were their feelings... For they ran in with tears, at 4:00, to wake me up, because this was beyond sleep. How wonderful! And this is what I thought... what sleep could there be!”

Nekrasov took the manuscript over to Belinsky. After reading it, Belinsky was delighted and greeted Nekrasov with the words: “Bring him over quickly!”

“And so I was brought over,” – relates Dostoyevsky in one of the volumes of the “Writer's Diary,” – “Belinsky greeted me very solemnly and with restraint. But not even a minute passed before everything was transformed: his solemnity was not that of an important person, a great critic, but out of respect so-to-speak for those important words which he hurried to say to me. I left his house in rapture. I stopped at the corner of his house, looked at the sky, at the bright day, at the passersby, and with my entire being I felt that an important moment had taken place in my life, that something began that was totally new, but which I had not imagined even in my most passionate dreams. Oh, I will be worthy of those praises, – and what people they were!”

With his subsequent literary career Dostoyevsky proved that Belinsky was not mistaken in recognizing a major prominent talent in the young writer.

However, the novel, though accepted enthusiastically, was not published right away, and Dostoyevsky continued to be in need of money. He already began a new novel, being fully aware that “literary work cannot be forced.” Unfortunately, throughout almost his entire life Dostoyevsky felt this hammer of need over himself, which forced him to sometimes write hurriedly and even change the broad plans of his works. Dostoyevsky's letters, published after his death, eloquently speak of the great penury which the writer, who represented the pride and glory of literature, was forced to endure at times. These same letters also explain to some extent the reasons for Dostoyevsky's financial situation. I am getting somewhat ahead of myself, but it is necessary. After the death of the older brother Mikhail, his family remained without any resources and with a mass of debts. Dostoyevsky took all the debts upon himself and supported his brother's family. Moreover, he helped many people, and taking care of his stepson Pavel Isayev (the son of his first wife, who married Dostoyevsky when she was already a widow) also cost him a lot. He helped his stepson generously, being concerned for him as for his own. All of this naturally portrays Dostoyevsky as a person with a charitable heart and a kind soul. He himself endured a great deal, in order for others to live more easily.

But let us go back.

Fate had prepared a terrible blow for the young writer who had begun his literary career so brilliantly. Dostoyevsky was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter-and-Paul Fortress. You may well ask for what? For having joined a circle of young men who were carried away by false teachings on state establishment and the situation of the people. Initially Dostoyevsky was not allowed to read or write; but two months later he was given the opportunity to read and to work... Many other individuals were arrested at the same time as he was. The attitude of the guard assigned to the prisoners was remarkable. At times, opening the little window in the door of the cell, he would say: “Are you bored? Well, endure it then! Christ endured too!” And Dostoyevsky did endure his imprisonment patiently. By the way, he wrote to his brother from the fortress: “I am not despairing, I have some activities. I have thought of three stories and two novels, one of which I am writing. I am engaged in reading here: two accounts of travels to holy places and the writings of St. Dimitry of Rostov; the latter have greatly engaged my attention.” In another letter Dostoyevsky asked his brother to send him a Bible.

The court sentenced Dostoyevsky, together with others, to be executed, but Tsar Nicholas I replaced the execution with hard labor. On Christmas Eve Dostoyevsky, together with the poet Durov, were sent to Siberia. The brothers' farewell was very moving. And this farewell demonstrated the wonderful traits of Dostoyevsky's soul. First of all, he expressed his joy that his brother did not suffer together with him (although he had also been arrested), and warmly and caringly asked his brother about the latter's family, especially his children, and entered into all the details of their health and activities. Mikhail Dostoyevsky could not refrain from crying, but Dostoyevsky was calm and comforted him: “The labor camps also consist of people and not animals, who are perhaps even better than I am. We will see each other again, I have great hope of this, and I don't even doubt that we will see each other. And after I leave the labor camp, I will start to write. During these months I have lived through a lot, and there in the future, whatever I see and live through... there will be a lot to write about.” He believed that even in the most hardened criminals, in fallen people, the spark of God was not extinguished. Weak in body, even half-sick, Dostoyevsky did not lose heart, because he did not cease being a Christian even for a single moment. Not only did he himself bear his punishment with fortitude, but he also served as a comforting angel to a weak comrade in misfortune.

Dostoyevsky's presentiments did not disappoint him: he did see his brother again. After Tsar Alexander II came to the throne, Dostoyevsky, who had already served out his sentence, returned to St. Petersburg. Restored in all the rights of which he had been deprived by exile, he once again began to serve his homeland as a writer. “And whatever I see there... there will be a lot to write about,” – he had said as he parted from his brother. Yes, he did see a lot and lived through a lot, and he described it all in his Notes from the House of the Dead. He portrays himself in them under the fictitious name of a nobleman sentenced to hard labor for the murder of his wife. Notes from the House of the Dead turned out to be a real event in literature. They revealed to the readers a whole world of people of whom they either knew nothing, or had a false idea. In reading the Notes, you inadvertently become convinced that even in the vilest reprobate the spark of goodness has not been extinguished, and God has not died in his soul. One must only understand the person, know how to touch his heart, and this spark will flare up again.

Dostoyevsky's return from Siberia practically coincided with the emancipation from serfdom of those millions of “lesser brethren,” for whom Dostoyevsky sorrowed prior to his exile and whom he loved since his childhood. No wonder he wrote to A.N. Maykov after his return from the labor camp: “I am akin to all things Russian to such an extent that even the convicts did not frighten me, since they were Russian people and my comrades in misfortune.”

An extensive and dynamic literary career began. Dostoyevsky continued to write novels and stories, published and edited magazines (Time and The Epoch) together with his brother Mikhail, and towards the end of his life he began publishing his Writer's Diary. The entire educated Russia listened keenly to the voice of the great literary artist and thinker, fervent patriot, and deeply religious Christian. Both old and young went to him and wrote to him, turned to him as to a teacher who had lived through a lot, had thought out a lot, ardently loved the truth and his homeland, and who could give advice and resolve various issues. Dostoyevsky did not tire of conversing with people, replying to letters, and instructing beginning writers. While remaining a literary artist in his novels, in his Writer's Diary Dostoyevsky was an essayist who fought for the truth, and who tried to make those who were in error see reason, to protect children from injustice, and to stand up for “the humiliated and the insulted.”

Having borne so much in life, but not having lost his faith in people, already ill and burdened by a family from his second marriage, Dostoyevsky worked doggedly like a young man, felt everything ardently, and was as excited as a youth. He reached out towards everything that was good without sparing himself, and did everything he could for those who needed his help. Despite his illness, he always willingly took part in the literary soirees that were organized for the benefit of young students, and read with innate ardor from some of his works... However, penury did not leave him entirely. He already had the opportunity of buying a small house in Staraya Russa, in order to spend summers outside of St. Petersburg in his own place, but even here he worked tirelessly, often sitting at his writing desk the entire night.

In 1880 Russia put up a monument to its brilliant bard of “Poltava,” who had died in 1837 at the hands of a French villain. In Moscow, where the monument to Pushkin was erected, there was a great celebration. Many people from all corners of Russia came to Moscow for the opening of the monument. Those were Pushkin's Days, that was Pushkin's holiday. But at the same time it was also Dostoyevsky's holiday, a celebration of the author of The Poor Folk. At a conference of the “Literary Society,” in the presence of a multitudinous audience, Dostoyevsky gave a speech on Pushkin. As soon as he began talking, the entire audience stirred and then went quiet. Dostoyevsky spoke with his usual force and simplicity. Above the huge quiet crowd the voice of Dostoyevsky sounded like the voice of some oracular prophet. When he finished – everyone was joyously excited. Delight was expressed noisily and spontaneously. People flung themselves at Dostoyevsky to kiss him. At the end of the conference, ladies suddenly appeared on the stage with a huge wreath. Dostoyevsky was asked to go on stage, while the wreath was held behind him like a frame, and the applause of the entire hall did not die down for a long time. Thus was feted the writer who was an ardent admirer of the prophetic poet, – the writer whose words also excited thousands of hearts, invoking goodness and light.

And in the meantime, death was already near. Feted at the Pushkin celebrations, in June of 1880 Dostoyevsky resumed work with his former energy and died like a soldier at his post. For the last 9 years he had suffered from emphysema as a result of a respiratory tract illness. The fatal outcome of the illness occurred due to the rupture of the pulmonary artery, and none of the physicians foresaw such a contingency. Dostoyevsky unexpectedly had a nosebleed, to which he did not pay attention. The next day there was bleeding from his throat. It happened again in the presence of the doctor, and to such a degree that the patient lost consciousness. Coming to, he expressed his wish to have confession and receive communion. While waiting for the priest, Dostoyevsky bid farewell to his wife and blessed his son and daughter. After communion Dostoyevsky felt better. The next day he could listen to the reading of newspapers. He continued to be concerned for the Writer's Diary, and he asked his wife to read the proofing of the January volume of the Diary. He wanted the Diary to come out as scheduled. This was the last volume, because on January 28, at 8 P.M., Dostoyevsky passed away.

The entire reading Russia felt a terrible loss. Everyone was stricken by the death of the beloved writer. With him died not only a great artist, but a friend and mentor.

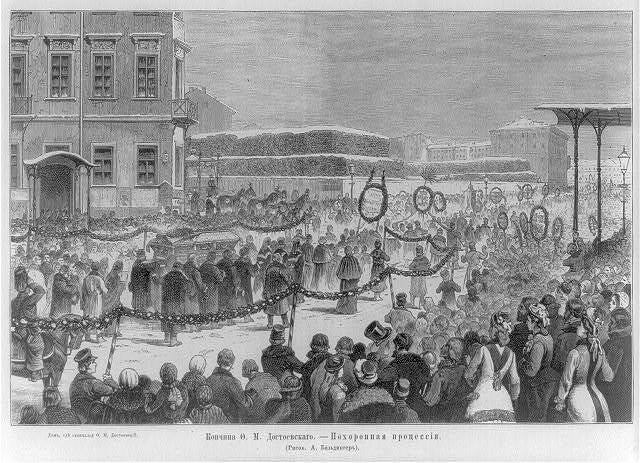

Never yet was a writer interred so ceremoniously in Russia, as Dostoyevsky was interred. A crowd of many thousands gathered to escort his remains. As the casket was being carried out of the apartment to the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, there were up to 70 wreaths, and 15 choirs of singers sang in the funeral procession. These were not hired singers; these choirs consisted of the deceased's admirers. People of diverse classes, ages, and views followed the casket, – there were many young people, to whom the deceased writer had told so much bitter truth. He loved these young people and – wishing them good – treated them like a sincere friend and kind mentor. And young people understood him and loved him. A crowd of twenty thousand followed the casket of a former labor camp inmate and now glorious writer; the funeral procession extended for two miles. An entire alley of wreaths, raised up high, disappeared into the distance. It was a sea of greenery. For the last time the Russian people put wreaths on the one who loved Russia so ardently and wholeheartedly, and who served it for such a long time and so honorably with his powerful word. Many speeches were said and poems were read at the grave. By the way, the young poet A.V. Arseneyev, now also deceased, read the following poem, which, though weak in form, breathed with sincere feeling:

“A heavy mortal hour has stricken Russia,

Its sound resounding painfully in our hearts –

A great man was extinguished prematurely,

A stream of great words was cut off untimely.

Our departed genius! His pure and crystal soul

Embraced the teaching of Christ's justice,

And to the weak humiliated lesser brethren

The words of holy love and sympathy he spoke!

O part, ye tombs that are adorned with glory,

Accept a new tomb into your immobile row,

Our majestic genius has come into your quiet midst,

For whom all our hearts have flamed with love.

Do sleep, our genius! It is not bitter envy,

But purest heartfelt love that buries thee here.

From here we all depart with sorrow in our hearts,

While here upon thy ashes our hottest tears do fall.”

Thus the people honored their beloved writer. He was not forgotten by the Sovereign either, who acknowledged his achievements. A pension was granted by the Sovereign to Dostoyevsky's widow and children. At that time it was an exceptional favor, since writers, as non-working people, did not receive pensions.

Many years have passed since Dostoyevsky's death. A wonderful tombstone was erected at his grave in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra by his admirers. But he himself erected the best tombstone for himself by his immortal writings and by his life, which one cannot but ponder. Judge for yourself. Fate sent him a terrible lesson. A labor camp and moral and physical suffering in his youth. Then a struggle with penury, years of a hard life and constant work without any rest... And he endured it all, overcame it all, and did not compromise his integrity, but vigorously and honorably served his homeland. His friend Strakhov was right in saying: “Yes, Dostoyevsky was not only a literary writer, but also a teacher. And not only a teacher, but a real hero in the literary field.”

I write these lines in Staraya Russa, where Dostoyevsky used to live and where there is now a school named after him... Hundreds and thousands of children will receive an education in it, will come to love books, and will come to love the writer whose portrait hangs in their school... They will read this anthology as well, which was compiled for all Russian children, for whom Dostoyevsky always cared so much.

He has died, but he lives on in his writings and converses with you through them, my friends. Pay heed to his words: – there is a lot to learn from him.

Alexander Kruglov.

1896, July 30.

Staraya Russa.

With many thanks to Dr. Raffaella Vassena, for kindly making the original available to us, and to Matushka Natalia Sheniloff, for the translation.

Forthcoming on this blog. (Ed.)

This story will be included in the next volume. (Author’s note; unfortunately, the aforementioned Russian volume never came out, as far as we are aware, but the story was included in the Romanian printed edition of Dostoevsky for Parents and Children (RDPC) and is forthcoming on this blog - ed.)

Will be included in the second volume. (Author’s note, but see above, n.3; forthcoming on this blog - ed.)

Relevant excerpts forthcoming on this blog. (Ed.)